Good to hear from you and especially about those fine old-time Ackley Improved cartridges. As you know, Ackley was far ahead of his time…and far ahead of all the commercial cartridge companies in improved design. He was our last great cartridge experimenter who could and did write about his work. Today we seem to have arrived at a point where we have experimenters and we have writers, but the two almost never meet! The great Ackley handbooks, Volume I & II, Handbook For Shooters & Reloaders, is in need of updating, but it would be a major undertaking and would require the input of some top experimenter and/or writer. If you inspect the loading data in those two books you will immediately notice the outdated, discontinued powders and the fact that he almost never gave barrel lengths along with velocities. Also, a number of the cartridges in Ackley’s books listed data from other sources such as directly from the designer who estimated most velocities, optimistically. But in spite of these minor disparages, Ackley’s books are still the experimenters bible, just loaded with technical information not found elsewhere.

Before getting into your questions concerning the Ackley cartridges with the best percentage improvement, smallest improvement and the ones left in the middle, perhaps you would have an interest in Ackley’s background…just to pass on to your friends in the hot stove league involved in the Ackley arguments during cold winter days. Parker O. Ackley was born in Granville, New York, graduated from Syracuse University in 1927 and nine years later started his first gunsmithing business in Roseburg, Oregon, 1936. He was with the Ordnance Department during World War II and then moved on to Trinidad, Colorado to open what was to become one of the largest custom gun shops in the country. He also taught at Trinidad State Junior College where his gunsmithing school became world famous. He moved on to the Salt Lake City, Utah area where he continued his shop and did a great deal of experimental gun work. Along the way he became widely known as a gun writer where he passed on his knowledge of the trade. He left us all in 1989 at the ripe old age of 86.

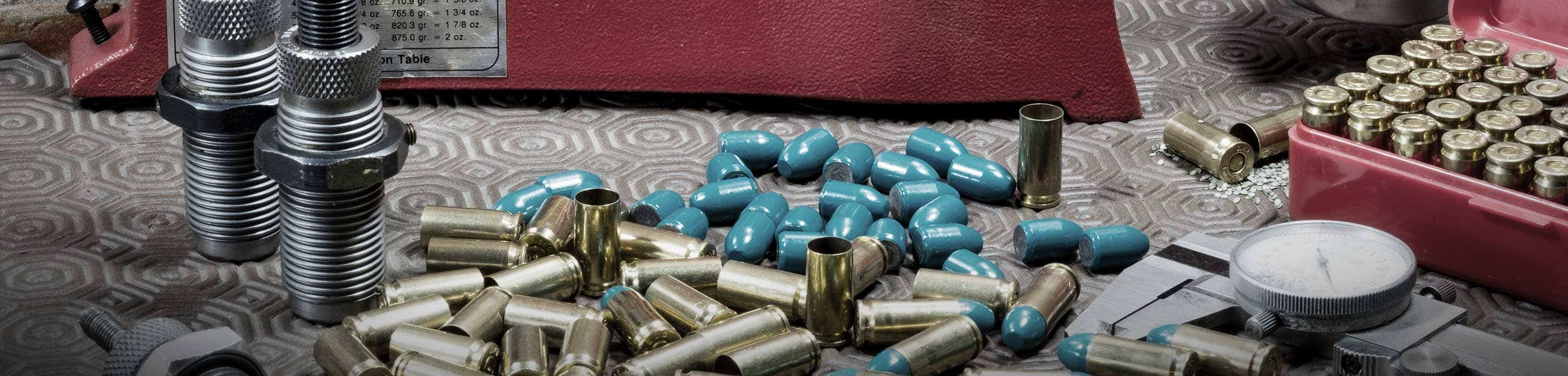

The first cartridges designed by Ackley in the so-called Improved shape simply straightened out the tapered case body, giving the original factory designs a more straight walled dimension and leaving the shoulder angle the same. While this proved to reduce back thrust on the bolt, it still showed some case stretching in the neck and shoulder area that resulted in continued case trimming. When he changed the shoulder to something like 30 degrees the case lengthening slowed and by the time his designs reached 40 degree shoulders, all case lengthening stopped, within reason. It became common to reload those cases 15 – 20 times without having to trim them. Thus, the benefits of the famous Ackley Improved cases became reduced back thrust and elimination of case trimming. Case extraction became easier and more positive and loading pressures could be increased safely, resulting in higher velocities. Another interesting feature of these Improved chambers is the fact that standard factory cartridges can still safely be fired in the rifle. There are some die makers that still offer Ackley dies with the milder shoulders, so when ordering loading dies it is prudent to specifically request the 40 degree shoulder model.

Now to get on with your questions. There are more than 20 Ackley Improved cartridges, plus dozens of Ackley Wildcats, but some have about gone into obsolescence because the parent cartridge is no longer being loaded by the factories. Thus, brass is difficult to find. Of those that are alive and well today, the percentage of velocity gain over factory loadings ranges from about 3% up to 17%. A couple of others exceed this gain, but the parent cartridges are no longer being chambered for by the rifle companies. When we compare the Ackley Improved cartridges to handloaded standard factory rounds, the velocity gain ranges from zero up to a little over 12%. From this you can see there are a few Ackley Improved cartridges that may not be worth the trouble and expense to chamber for. But on the other hand, there are several that will simply blow you away with their new velocities, especially when compared to some of the much larger factory belted magnums, the big boomers.

There are many sources of cartridge velocities available today. These include factory listings as well as the dozen or so reloading manuals. This means there are many different barrels being used to arrive at those velocities. And that is why we, as handloaders and experimenters, must utilize several loading manuals in order to arrive at some norm that can be our starting point. When searching for the proper velocities to pass on to you to answer your questions, I first took the factory listed data from several cartridge companies and used their best figures. Then I utilized Ackley’s book figures, plus data from various other sources where barrel length and chronographed velocities were shown. This meant that some information differs from that found in Ackley’s books due to using new powders, stating the barrel lengths and chronographing over electric chronographs instead of the old pendulum style used so often by Ackley. In all cases pressures could only be observed by common shooter’s methods, that is, by checking primers, primer pockets, case heads, extraction, case life, etc. Generally, pressure guns using the crusher-gage method and resulting in copper units of pressure (c.u.p.) are not available outside the ballistics labs. This is also basically true of the more modern electronic-transducer gages that record in pounds per square inch (p.s.i.). These methods of discovering chamber pressures result in disabling the rifle by drilling into the chamber or at least attaching wires to it. It should be remembered that pressures given in c.u.p. are somewhere around 15% lower than those found in p.s.i. recordings, and when using various books giving pressures be sure to notice when two different methods are being used.

The best velocity gain of all the Ackley cartridges compared to the standard factory cartridge comes with the .25-35 WCF with a 117 gr. bullet and a gain of about 25.6%. The second best is the .30-40 Krag and the 180 gr. bullet showing a velocity gain of 19.3%. Both are rimmed cases and neither one is being chambered for today. Therefore, we will start with the third best velocity gain of 17% as found with the little .250 Savage when converted to the Ackley configuration and loaded with the 100 gr. bullet. Our rifle companies have chambered for the .250 Savage from time to time, but it is rapidly becoming obsolete in spite of the many knowledgeable shooters who use it regularly. The factory .250 Savage load is 2820 fps, while the .250 Ackley attains close to 3300 fps. This little speedster can equal or exceed the factory velocity of the much larger .25-06, listed at 3220 fps. And it is being done with 15 – 20 grs. less powder which means a great deal less recoil for the same velocity and trajectory. This is downright amazing…. And all this is being done in a short action. This .250 Ackley cartridge is not shown in any modern reloading book that I know of. Some books do show another .25 caliber, the .257 Ackley, that lands farther down the line in eighth place for best Ackley percentage gainers. I have used the .250 Ackley for both varminting and big game hunting with outstanding results.

Before getting into your questions concerning the Ackley cartridges with the best percentage improvement, smallest improvement and the ones left in the middle, perhaps you would have an interest in Ackley’s background…just to pass on to your friends in the hot stove league involved in the Ackley arguments during cold winter days. Parker O. Ackley was born in Granville, New York, graduated from Syracuse University in 1927 and nine years later started his first gunsmithing business in Roseburg, Oregon, 1936. He was with the Ordnance Department during World War II and then moved on to Trinidad, Colorado to open what was to become one of the largest custom gun shops in the country. He also taught at Trinidad State Junior College where his gunsmithing school became world famous. He moved on to the Salt Lake City, Utah area where he continued his shop and did a great deal of experimental gun work. Along the way he became widely known as a gun writer where he passed on his knowledge of the trade. He left us all in 1989 at the ripe old age of 86.

The first cartridges designed by Ackley in the so-called Improved shape simply straightened out the tapered case body, giving the original factory designs a more straight walled dimension and leaving the shoulder angle the same. While this proved to reduce back thrust on the bolt, it still showed some case stretching in the neck and shoulder area that resulted in continued case trimming. When he changed the shoulder to something like 30 degrees the case lengthening slowed and by the time his designs reached 40 degree shoulders, all case lengthening stopped, within reason. It became common to reload those cases 15 – 20 times without having to trim them. Thus, the benefits of the famous Ackley Improved cases became reduced back thrust and elimination of case trimming. Case extraction became easier and more positive and loading pressures could be increased safely, resulting in higher velocities. Another interesting feature of these Improved chambers is the fact that standard factory cartridges can still safely be fired in the rifle. There are some die makers that still offer Ackley dies with the milder shoulders, so when ordering loading dies it is prudent to specifically request the 40 degree shoulder model.

Now to get on with your questions. There are more than 20 Ackley Improved cartridges, plus dozens of Ackley Wildcats, but some have about gone into obsolescence because the parent cartridge is no longer being loaded by the factories. Thus, brass is difficult to find. Of those that are alive and well today, the percentage of velocity gain over factory loadings ranges from about 3% up to 17%. A couple of others exceed this gain, but the parent cartridges are no longer being chambered for by the rifle companies. When we compare the Ackley Improved cartridges to handloaded standard factory rounds, the velocity gain ranges from zero up to a little over 12%. From this you can see there are a few Ackley Improved cartridges that may not be worth the trouble and expense to chamber for. But on the other hand, there are several that will simply blow you away with their new velocities, especially when compared to some of the much larger factory belted magnums, the big boomers.

There are many sources of cartridge velocities available today. These include factory listings as well as the dozen or so reloading manuals. This means there are many different barrels being used to arrive at those velocities. And that is why we, as handloaders and experimenters, must utilize several loading manuals in order to arrive at some norm that can be our starting point. When searching for the proper velocities to pass on to you to answer your questions, I first took the factory listed data from several cartridge companies and used their best figures. Then I utilized Ackley’s book figures, plus data from various other sources where barrel length and chronographed velocities were shown. This meant that some information differs from that found in Ackley’s books due to using new powders, stating the barrel lengths and chronographing over electric chronographs instead of the old pendulum style used so often by Ackley. In all cases pressures could only be observed by common shooter’s methods, that is, by checking primers, primer pockets, case heads, extraction, case life, etc. Generally, pressure guns using the crusher-gage method and resulting in copper units of pressure (c.u.p.) are not available outside the ballistics labs. This is also basically true of the more modern electronic-transducer gages that record in pounds per square inch (p.s.i.). These methods of discovering chamber pressures result in disabling the rifle by drilling into the chamber or at least attaching wires to it. It should be remembered that pressures given in c.u.p. are somewhere around 15% lower than those found in p.s.i. recordings, and when using various books giving pressures be sure to notice when two different methods are being used.

The best velocity gain of all the Ackley cartridges compared to the standard factory cartridge comes with the .25-35 WCF with a 117 gr. bullet and a gain of about 25.6%. The second best is the .30-40 Krag and the 180 gr. bullet showing a velocity gain of 19.3%. Both are rimmed cases and neither one is being chambered for today. Therefore, we will start with the third best velocity gain of 17% as found with the little .250 Savage when converted to the Ackley configuration and loaded with the 100 gr. bullet. Our rifle companies have chambered for the .250 Savage from time to time, but it is rapidly becoming obsolete in spite of the many knowledgeable shooters who use it regularly. The factory .250 Savage load is 2820 fps, while the .250 Ackley attains close to 3300 fps. This little speedster can equal or exceed the factory velocity of the much larger .25-06, listed at 3220 fps. And it is being done with 15 – 20 grs. less powder which means a great deal less recoil for the same velocity and trajectory. This is downright amazing…. And all this is being done in a short action. This .250 Ackley cartridge is not shown in any modern reloading book that I know of. Some books do show another .25 caliber, the .257 Ackley, that lands farther down the line in eighth place for best Ackley percentage gainers. I have used the .250 Ackley for both varminting and big game hunting with outstanding results.