The Madsen was a very late bolt-action rifle, designed for Third World countries which couldn't afford modern automatics. I don't believe anybody but Columbia bought it. It is probably accurate enough, that is a very bad place to put a peepsight, because the bolt makes it difficult to put it further back, and the lever isn't convenient for rapid fire. when I saw them advertised in "American Rifleman" in the 60s, their principle merit was that they were nearly new, and still cheap.

The Boer War of 1899 could be said to be won by rifle fire, although it was lost, by attrition and lost ability to supply, by the side which started out the best riflemen. No more recent large war has been won by rifle fire, and few armies nowadays expect better or longer-range accuracy than could have been achieved with a well-cleaned and well loaded Minié rifle. I doubt if any army expects its run-of-the-mill soldier to do much windage adjustment in the field, or make much use of the rifle at over 300 yards. At that distance, few soldiers will do better with windage adjustment than they would by knowing the sort of conditions and range which require a half or full body width of wind allowance.

Probably the best large force of riflemen were the British Expeditionary Force of 1914. But they weren't trained to chase wind deflection in the field. That was for the range, and in the Second World War every unit armourer having a screw foresight adusting tool, rather than a hammer, worked just fine.

Somewhere around 1968, on a target range, I saw some impeccably equipped young men laughing at an old man in a crumpled raincoat, with pebble glasses, who had made a group bout the size of a soup-plate at 200 yards, with a completely standard SMLE. He phoned the firing-point, told them to leave a target up, and did the same, no better but no worse, ten times in a quarter-minute. I've seen Germans on TV, in 1963, telling how their units were swept away at nine hundred.

I've also had old men tell me how they picked up wounded student volunteers who admitted to having no military training whatsoever, and seen tears in their eyes they would never have shown for their own, because the German emperor had used them to do murder. A lot of good Mausers (or perhaps more likely the rather satisfactory M1888 Commission rifle) did them. TF Fremantle, who had a lot to do with the design of the .303, said the French believed that because all divisions were turning in the same rifle scores, the limits of rifle accuracy had been reached. The Germans, he said, believed that as soldiers always shoot inaccurately to some extent, giving them a perfectly accurate rifle would make them miss all the time, instead of only part of it.

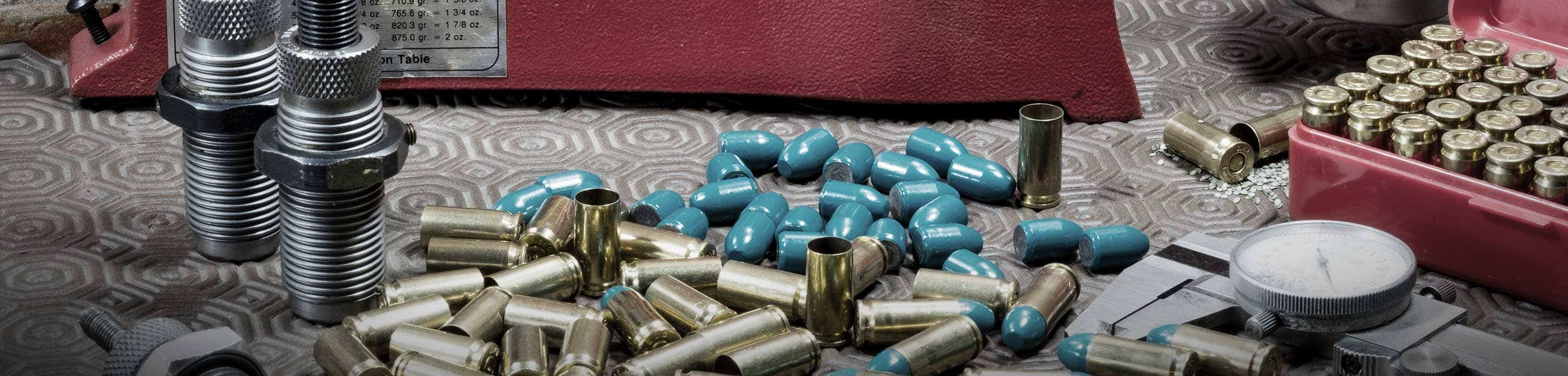

No. 4 Lee-Enfields sometimes had excessive groove and neck diameters, and unlike most defects of military rifles this wasn't associated with wartime emergency or poor finish. Late wartime ones are often better in this respect. But reloading with larger bullets - e.g. 318 J-bore Mauser bullets sized appropriately, or in the worst cases just as they come, made a great difference to accuracy and brass life. (This requires caution, since although I have never heard of one having an oversize groove diameter and not an oversize neck, you might, and oversize bullets could cause that chamber to clamp the neck tightly onto them.)

There were inaccurate M1903 Springfields in wartime production too. Incidentally I don't believe a thing in the Springfield can be attributed to the 98 rather than 93 to 96 Mausers In particular it lacks the stop-ring inside the receiver ring, which if you do get a ruptured case-head, makes the Mauser pretty safe when made of mild steel. As a matter of fact not a thing in the Springfield (front locking, rear lever, solid receiver bridge, Lee's clip-loading magazine etc.) wasn't used by Mannlicher on different, mostly experimental rifles. The Springfield could have come together without the Mauser brothers.

If we are talking about a military rifle to be used for military purposes, just as it comes, I think it has to be the P14 or M1917 Enfield. It needed to be shorter and lighter, and with less urgent need would surely have become so. But its big advantage, and what caused General Hatcher to call it the best First World War military rifle, was its correctly placed and well protected peepsight, the first even attempted in a mass production military rifle. It could still be seen, in simplified form, in the early M16. I don't believe anybody in the West went for an all-new rifle with anything else. Fast, foolproof aim, including in rain or poor light, does far more for even an above-average rifleman than anything twiddling knobs can do.

If, on the other hand, we are talking about what the modern civilian rifle enthusiast can do with a rifle or its action, I think it has to be the 98 Mauser. Among other advantages come the availability and usability of good modern scope mounts, micrometer peepsights, threaded barrels and triggers. The Springfield, with less availability of those, still makes as good a basic rifle. The P14 or M1917 accommodates a lot of cartridge, at the expense of a lot of gunsmithing. I must confess I'd go for the Greek Mannlicher-Schoenauer, but that's probably just me. You would have to find something like the old external-adjustment Bausch and Lomb scope (about the earliest with modern-standard optics), in Kuharsky side-mounts, like I have on my civilian version.